1920’s Electric Memories

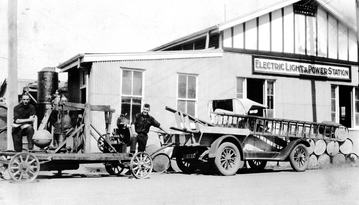

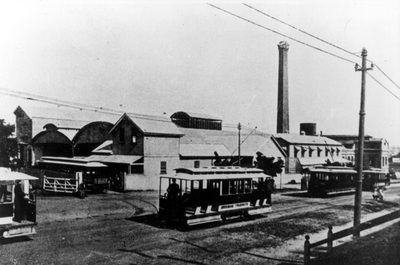

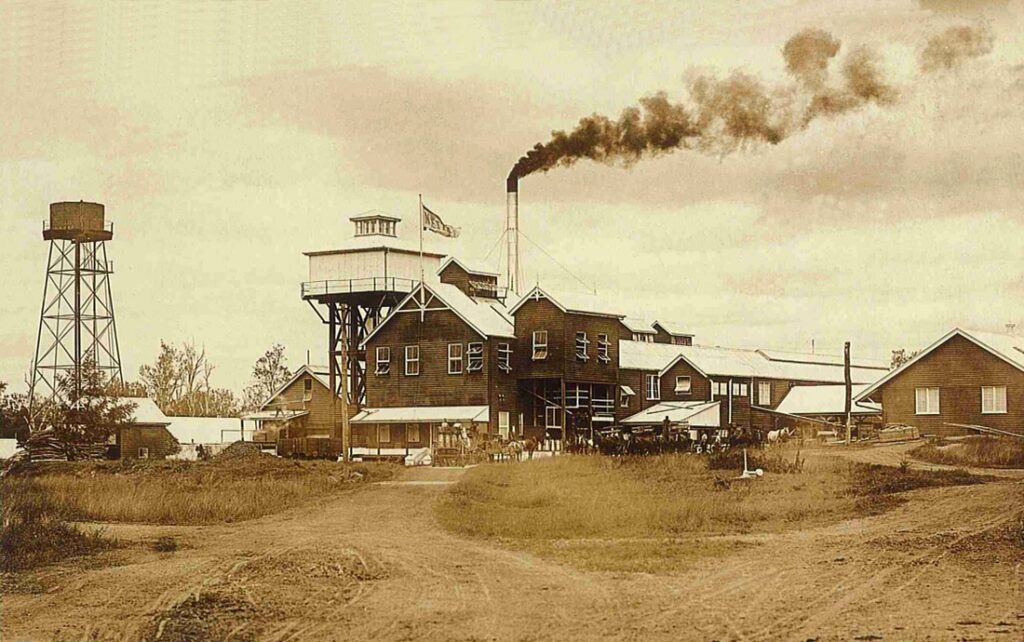

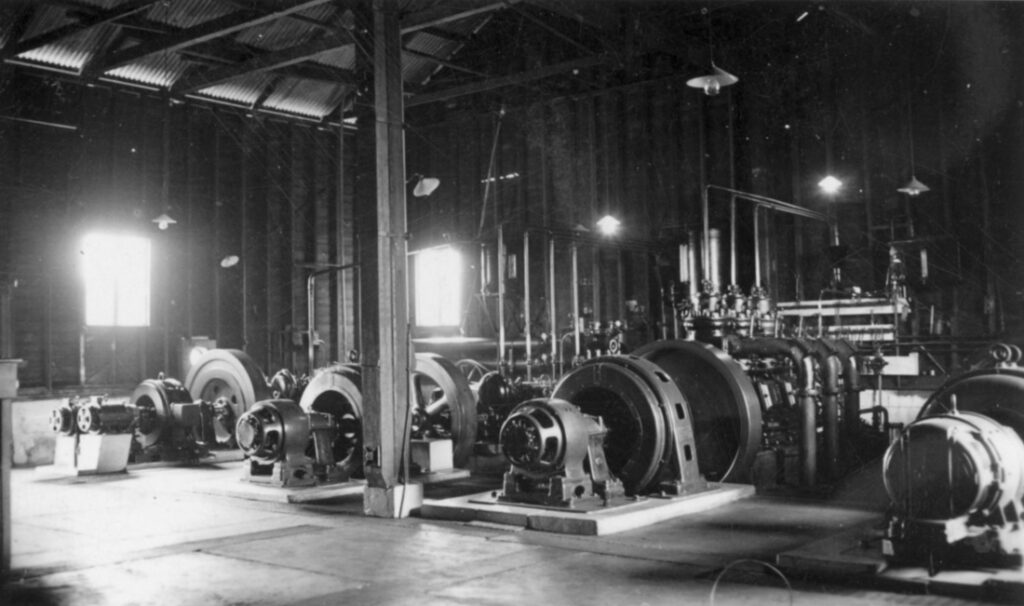

Dalby powerhouse 1921

1921

Electricity was first generated in Dalby’s Powerhouse in 1921 and on the day of the switch-on, there were 84 consumers.

Longreach Powerhouse was built in 1921 following four years of agitation by the Shire Council in an attempt to obtain a generating license and a State Government building loan. In part, the delay was caused by the insistence of the Longreach Shire councillors that the planned powerhouse should be larger than the one at Barcaldine, which was the only town in the Central West at that time to have a generating station.

Eagle Street in Longreach was alight with electric lights ready for the Christmas celebrations in 1921. Residential premises were connected soon after. At first, electricity was used only for lighting purposes. As more electric household appliances became available in Longreach from about 1925, the most popular items for local homes were irons, toasters and kettles. It was later in the 1950s that other electric appliances became more affordable to Longreach residents.

The Longreach Powerhouse generated Direct Current (DC) and was set to run continuously, day and night. In an effort to economise, the engines were often unattended from midnight through the early hours of the morning. Power was also shut off on moonlit nights when residents were expected to use the free light of the moon to go about their business.

Charcoal gas was used to power the engines. Timber was plentiful and labourers were easy to find in the early years of operation. However, during the Second World War, there were not so many people available to work. At that time, the Longreach Shire Council had to call for volunteers to cut and charcoal timber. Power outages were frequent. By 1952, the local timber was becoming sparse and orders were placed for the Powerhouse plant to be converted to run on coal gas.

The State Electricity Commission (SEC) was aware of the fuel issues associated with generating power in many parts of Queensland. Gas producers had been using wood or charcoal as the main source of fuel and a small amount of coke in some places. However, timber shortages were apparent and charcoal production had almost ceased. Accordingly, the SEC stated that coal would be adopted as the fuel for the powerhouses affected by the wood shortage. An alternative type of plant was also being investigated by the SEC and this was the gas turbine using pulverised coal. The cooling water needs of the plant being low, this type of plant, it was hoped, would be suitable for use almost anywhere in Queensland.

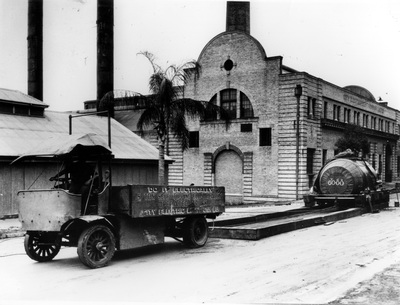

May 1922: Hubert’s Well, Townsville

The electricity supply was owned and operated by Townsville City Council and had been since 1 November, 1920, when the council was successful with an application for an Order-in-Council. The supply area took in the whole of the city limits except for Magnetic Island. The council was planning to apply for a further Order-in-Council to extend the supply area outside the boundaries of the city.

Electricity for Townsville was generated from the Hubert’s Well Powerhouse, which was the original water pumping station and was situated in the south-western section of the city. By 31 May, 1922, everything was ready for the Switch-on Ceremony at Hubert’s Well Powerhouse. Townsville’s Town Hall was the venue for the ceremony and a temporary switch was positioned on the balcony. When the Mayor pressed the switch, the streets were brilliantly lit, to the enjoyment and pleasure of the watching crowd.

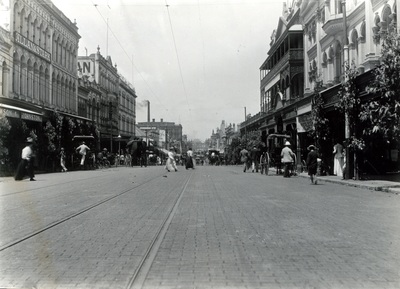

The wonderful change in Flinders Street was most marked, the bright lights in sets of four springing out of the darkness, and Flinders Street from a dimly lighted street became a brilliantly illuminated avenue right into the distance.

There were issues concerning the location of the powerhouse. The perceived problems included the distance from the load centre, difficulties with the foundations when installing large plant, the long haulage distance for coal from the Bowen Consolidated Coal Mine at Scottsville, which was ‘163 miles from Townsville by rail’ and the ongoing maintenance of the coal-siding at the powerhouse.

The lighting system provided for 358 street lamps of various candle power to illuminate 45 kilometres of streets. Altogether, the initial scheme included 1363 poles, 230 kilometres of cable, 2800 cross-arms, 7500 insulators and seven transformer substations.

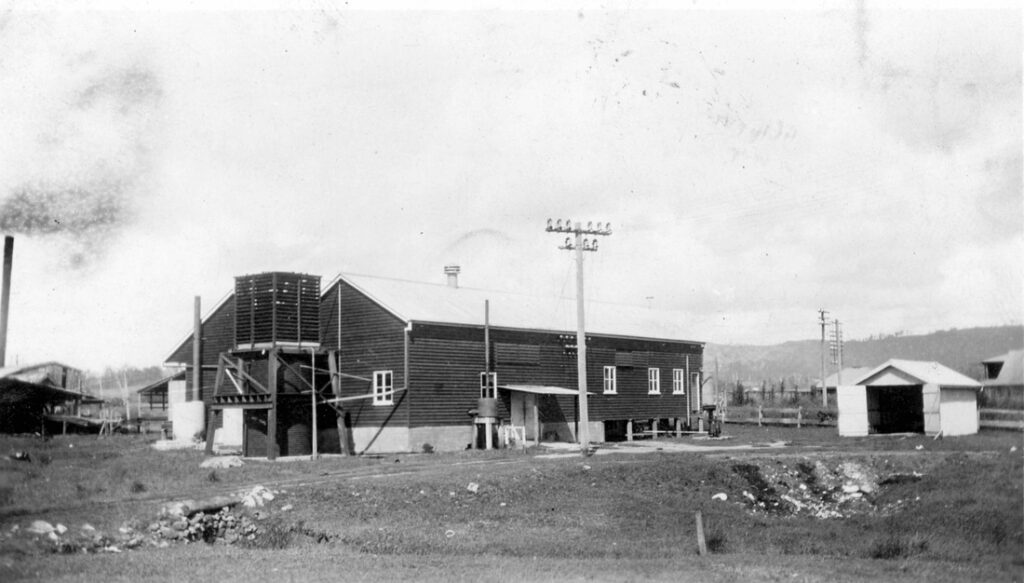

1922: Home Hill Powerhouse

Home Hill Powerhouse was different from other generating stations in North Queensland in that it was instigated by a Government body, the Queensland Irrigation and Water Supply Commission. Following an investigation by the Government in 1916 focusing on irrigation and the best means to supply water to farms in the Burdekin area, several wells were excavated and plans were implemented for an irrigation scheme, which would include an electricity supply for pumping and for lighting the town of Home Hill. The scheme was officially opened in February 1922. Home Hill was situated in the Inkerman irrigation area and, by 1939-1940 with this scheme, 186 farms were supplied with electricity and 407 in the town. The population in the supply area at that time was around 3,000.

The powerhouse was a considerable size after some additions to the plant, and by 1939 there were seven generating sets, comprising four large steam turbo-alternators and three smaller diesel sets. The request for assistance from Townsville and consequent discussions in 1942 led to the construction of a tie line, which linked the Townsville Hubert’s Well Powerhouse with the generating station at Home Hill in 1944. The over-loading experienced by the Hubert’s Well Powerhouse was not an isolated case in Queensland during the war.

1924: Goondiwindi Town Council

Goondiwindi Town Council inaugurated the electricity supply for the town in September, 1924. The plant at the Goondiwindi Powerhouse included a mixture of heavy-oil engines and wood-fuel gas producer engines, all coupled to generators providing Direct Current (DC) to 412 consumers out of a population in the supply area of 2,750.

Cairns City Council became an Electric Authority following the granting of an Order-in-Council on 16 November, 1923. The Cairns Electric Authority continued to operate until it was absorbed into the Barron Falls Hydro-Electricity Board.

The official Switch-on Ceremony for the city of Cairns was scheduled to take place on Wednesday, 14 January, 1925 at 8pm. A temporary platform was erected adjacent to the Koch Monument in the town and many people gathered for the ceremony. The Mayoress, Mrs. A.J. Draper performed the switch-on and to loud cheers from the crowd and a burst of tune from the brass band, the streets were brilliantly lit. To start the speeches, the Mayor of Cairns spoke about the preparations that were necessary to provide the city with electricity and promised to extend reticulation to other people who were not connected to the initial scheme. Other officials ready to speak were the Chairman of the Cairns Shire Council, Cr. S.H. Warner, the Harbour Board Chairman, Mr. W.C. Griffin, Chairman of the Cairns Chamber of Commerce, Mr. D.W. Olley and Mr. M.R. Cuthbertson, representing the electrical consulting engineering company, Messrs Christie and Reynolds. At the close of the official ceremony, Hides Hotel hosted a banquet to celebrate the successful electrification of the city.

The original plant at the Cairns Powerhouse was coal-fired. However, the cost of the coal limited output at a satisfactory economic price to meet the rapidly growing requirements of industry and the general population. It was decided that it would be more beneficial and efficient to consider hydro-electricity development in the Cairns area than to add to the steam-driven plant at the Cairns Powerhouse.

1925: Kingaroy

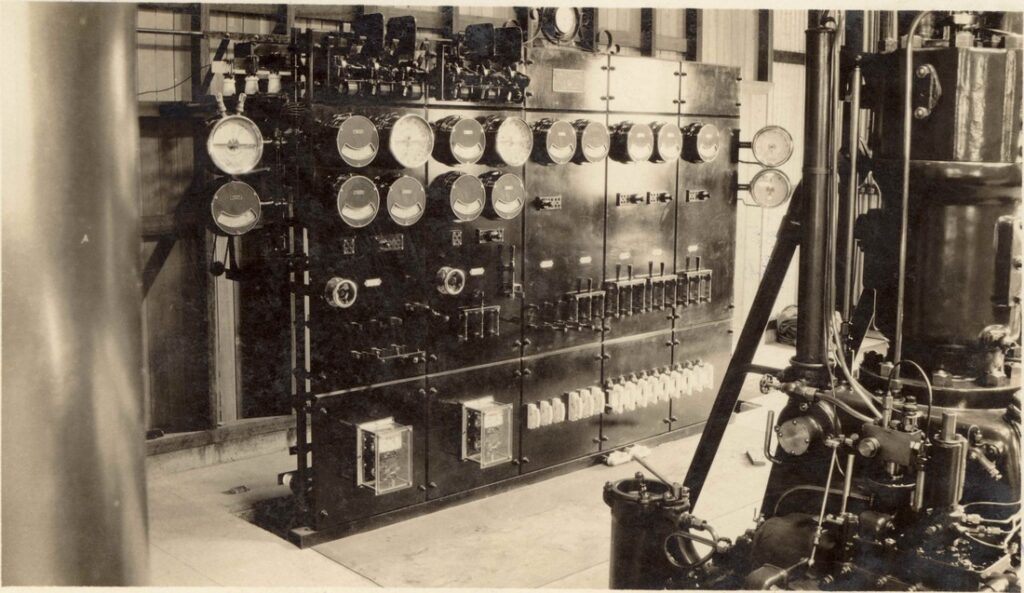

Kingaroy was the first town in the South Burnett to have electricity from its local Powerhouse. The plant comprised one twin cylinder suction gas engine and one single-cylinder suction gas engine, supplied by Ruston and Hornsby, England. In addition, the plant included an Akroyd wood-burning gas producer, a 40kW generator, a 10-kW generator, a six-panel switchboard and pumping equipment coupled to an electric motor.

Kingaroy Shire Council’s electric light and power scheme, which was operated from the Kingaroy Powerhouse, was officially celebrated with a Switching-on Ceremony on 28 January, 1925.

The Maryborough Chronicle covering the news item noted that people turned out in large numbers to honour the occasion. Mr. J.B. Edwards, M.L.A., turned on the power from a dais erected in front of the Shire Hall on the side nearest to the Powerhouse. In his opening speech, Mr. Edwards spoke of the conditions before electricity came to Kingaroy. His speech was followed by Mr. P.A.W. Anthony, who was representing the Consulting Engineer for the electricity scheme. Mr. Anthony offered some advice to the council regarding the scheme and then pointed out to consumers the various ways in which electricity could be utilised in the home and in industrial applications. He continued by encouraging everyone ‘to do all they could to increase the number of consumers, and so assist the council to reduce the price of current’.

The sentiments expressed by Mr. Anthony were repeated during the Smoke Concert, which followed the ceremony. Addressing the toast of the evening, ‘Kingaroy Electric Authority’, Mr. J.J. Grier, Government Engineer said that he was optimistic that the scheme would be a success. However, he stressed that consumers must co-operate with the Council in obtaining further consumers for lighting and for other purposes for which electrical energy could be used. Being involved ‘with every electric light scheme in Queensland, and Kingaroy was the 41st on the list’, Mr Grier acknowledged that other speakers had voiced similar opinions. However, he noted that an important perspective had been missed out so far. Women in the home would be able to experience a reduction in housework if electricity was used in as many conceivable ways as possible for domestic purposes. This would also help the council to meet its financial obligations.

1925: Brisbane

The Greater Brisbane Act was passed in October 1924 and on 1 October 1925 Brisbane City Council came into being. The new council became responsible for the control and administration of 20 towns and shires, which comprised the newly created City of Brisbane.

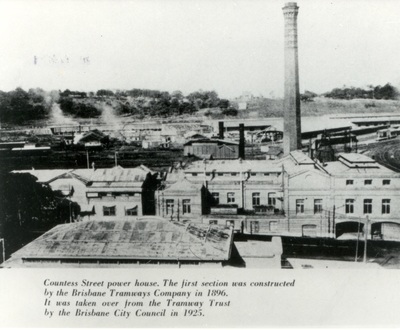

Franchises were held by a number of small councils granting the right to distribute electricity to residents within the respective council’s boundaries. Electricity was purchased in bulk, mainly from the City Electric Light Company (CEL), with a few councils supplied by the Tramways Trust, which was the successor to the Brisbane Tramways Co. Ltd. In 1923, these franchises were amalgamated under the Metropolitan Electricity Board. On 1 October 1925, following the passing of the Greater Brisbane Act, Brisbane City Council (BCC) was established and BCC’s Electricity Department took over the functions of the earlier Board. In December 1925, BCC also acquired the responsibility for the Brisbane Tramways Trust. CEL still maintained the right to supply in the old cities of Brisbane and South Brisbane.

One of the first topics the new council addressed was the best way to progress with electricity supply. Three main courses of action emerged for discussion: purchase the assets of the CEL, continue to buy electricity in bulk from the company, or build a new powerhouse. In March 1926, the BCC offered to buy the CEL’s assets for one-and-a-half million pounds. Mr. E J. Holmes, CEL’s Chairman, rejected the offer as being unfair. He claimed that BCC had little idea of the enormous scale of the undertaking. It was finally decided that BCC would build a new powerhouse at New Farm to supply the tramway system.

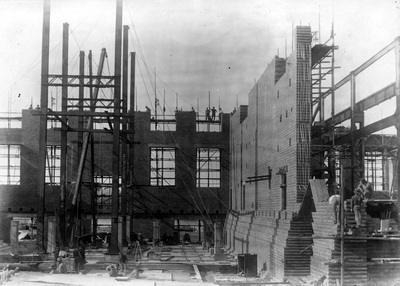

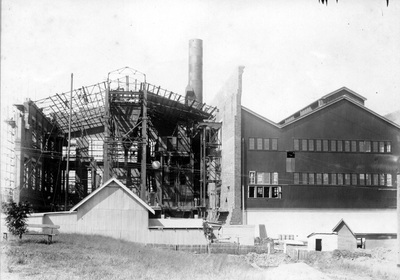

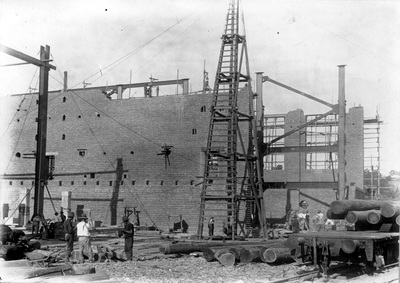

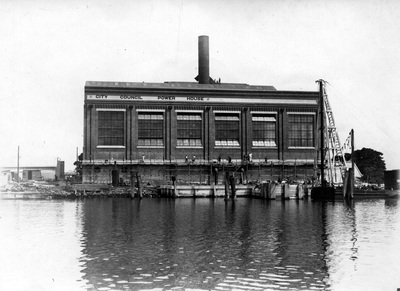

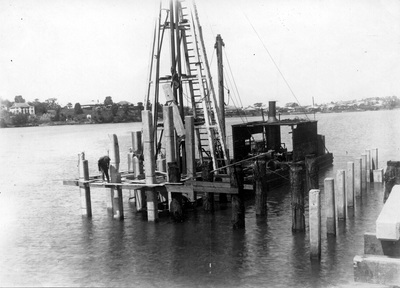

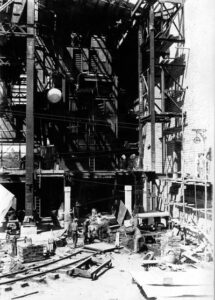

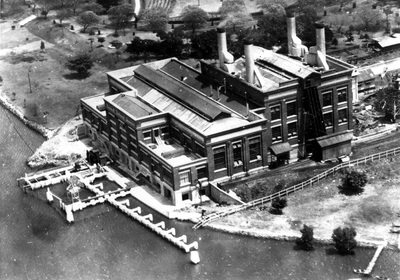

1926: Construction of New Farm Powerhouse

Although BCC operated other powerhouses for their tramways, New Farm was the first one to be constructed by them. Mr. R. Ogg, architect and construction engineer for BCC, designed the building elevation. In December 1926 the first test piles were driven to a depth of 55ft. (16.8m). More than 1,400 ironbark piles were forced into the ground using a 35cwt. (1.77 tonnes) ‘monkey’ hammer with a 7ft. (2.1m) drop. Each pile penetrated the soil barely 1 ½ ins. (3.8cm) after 7 blows, which suggests that they had been driven enough The piling operations were finalised by the end of March 1927 and construction of the buildings began. The powerhouse was finally commissioned in June 1928.

1926: End of William Street, new Bulimba Powerhouse

The William Street Powerhouse had come to its end. More capacity was required and a new Powerhouse was built at Bulimba and came into service in June 1926. However, there were some initial difficulties with the new operations, and this kept the William Street plant supplying power on occasions until 1930, when it was de-commissioned. The closure was brief, since the plant was called on again to generate power in 1931 due to the failure of submarine cables across the Brisbane River. Eventually, the remaining William Street plant was dismantled and most of it sold to Evans Deakin and Company.

From 1926, when the first unit was installed with a capacity of 12,500kW, Bulimba Powerhouse increased its installed capacity to 92,500 kW by the end of the Second World War in an attempt to keep up with the escalating demand for electricity.

Later, when a second power station was built at Bulimba – Bulimba ‘B’ Power Station – the original Bulimba Powerhouse became known as Bulimba ‘A’. The term ‘powerhouse’ was, and still is used, for the smaller generating stations, whereas ‘power station’ became the common terminology for the larger ones constructed after Bulimba ‘A’.

1927: Winton

The Winton Electric Authority was inaugurated by the Winton Shire Council in January, 1927. Prior to the council electricity scheme there was a private supplier for a short time. The council granted permission for Mr. F.H. Cooper to supply electric light within the town and ‘to carry cables across the street for that purpose’. However, supply was limited and in 1919, the council looked into the possibility of building a council-operated Powerhouse. Work on the Powerhouse was completed and the town’s power was switched-on by the Winton Shire Council’s Chairman, Cr. L. Irving in January, 1927 and DC current was supplied to the town.

By 1928, the Powerhouse plant was overloaded and only half of the town was reticulated. Applications for lighting were being received regularly. The plant’s capacity was doubled in 1930 in an attempt to satisfy demand in the town. Managing the Winton Powerhouse from late-1927 to 1939, Mr. T.F. Warden-Hutton brought the operation of the plant to an efficient standard and promoted the use of reticulated electricity in Winton Shire, including in the local ice factory, wool-scouring plant and tanning works. By the end of 1935 there were 254 consumers in Winton. By 1940, the population in the supply area was 1780 and out of this number, there were 283 consumers supplied with electricity from the Powerhouse.

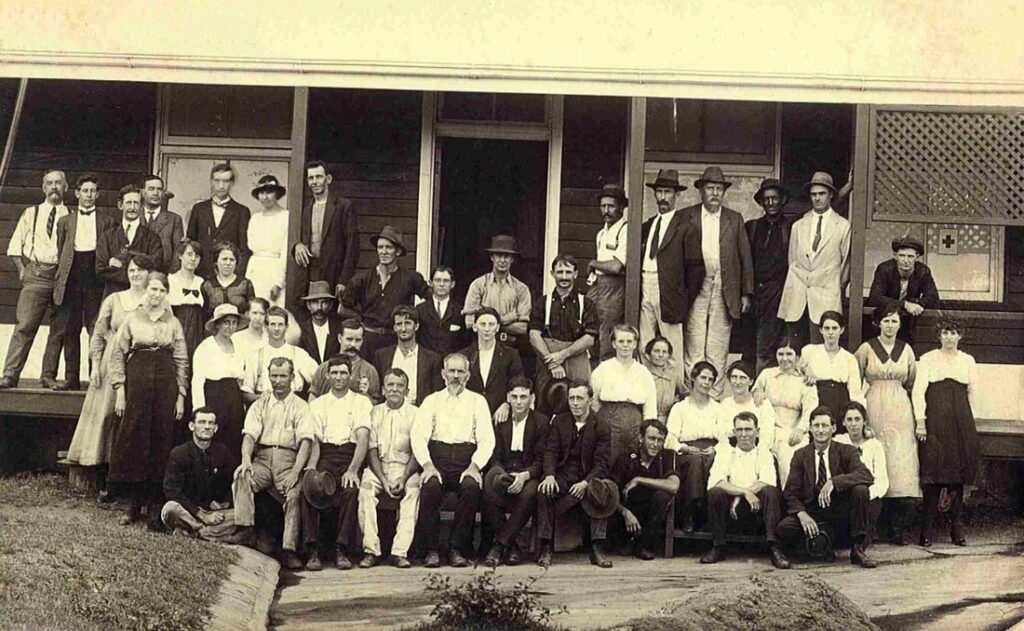

1927: Toogoolawah received electricity from Nestles

Esk Shire covered the three main towns of towns Lowood, Esk, Toogoolawah and surrounding areas. Lowood was supplied by IESCo and Toogoolawah received its first electricity supply earlier than Lowood from the Nestles Condensery on 20 June, 1927.

It was claimed that when Nestles offered to supply the town with reticulated water or electricity, the residents chose electricity. On the afternoon of 20 June, Mr. M.J. Kirwan, Minister for Public Works arrived in Toogoolawah with his Secretary, Mr. Bolger and Mr. Grier, Works Department Electrical Engineer. The party was welcomed by the Chairman of Esk Shire Council, Cr. A. Smith and a tour of the Nestles factory was undertaken with the Manager, Mr. A.C. Munro in attendance. Mr. Kirwan was impressed by the cleanliness of the factory and its excellent products. Following the tour, afternoon tea was served.

Several hundred Toogoolawah residents, Esk Shire Council members and visitors from nearby areas had gathered for the switching on ceremony, which was planned to take place at 5.45p.m. Mr. H. Frew, Esk Shire Council’s Consulting Engineer handed the key of the electric light board system in the Nestles Condensery to Cr. Smith, who called on Mr. Kirwan to declare the system open. Before doing so, Mr. Kirwan thanked the council for inviting him to attend the occasion, which, he said, marked a new era in the history of the town. He congratulated the townspeople for their endeavours erecting brick buildings in place of those destroyed in the ‘disastrous fires’ in April1926. It showed, he said, that the people of Toogoolawah had great faith in the future and he was certain that their town would progress. Mr. Kirwan invited Mrs Smith, wife of the Shire Chairman to officially switch on the electric lights for Toogoolawah. Mrs. Smith obliged enthusiastically while the crowd looked on happily and the Mt. Beppo Band played popular selections in the main street.

(Sources for Toogoolawah: Queensland Times, 21 June, 1927 ‘Electric Light System Switched On. Toogoolawah’s Gala Day’, with acknowledgement to the Toogoolawah & District History Group and Elizabeth de Lacy for supplying the history of the Nestles Condensery and the images)

The Brisbane Valley line was finished by the middle of 1936 and mains were being constructed to extend supply as far as Helidon, near Toowoomba. The line was also extended from Lowood to Esk and Toogoolawah. All rural charges for electricity were 10 per cent above those for Ipswich.

1927: Nambour Switch-on Ceremony

The Switch-on Ceremony in Nambour took place on Monday, 12 September, 1927. The first 118 consumers were provided with electricity as the switches were pressed. Some people observed that the glow from the electric lights was whiter than that of the yellow tinge of the light from kerosene lamps. By the end of the week, it was claimed that there were 240 consumers connected to electricity.

At a dinner to celebrate the coming of electricity to the town, Mr. W. Whalley spoke about the advantages of electricity to Nambour noting that it would brighten up the town in many ways. He said that Nambour had taken a practical step forward and passed another milestone in its history. He did warn that with it being a new project, there could be problems along the way. He remembered that when he was in Sydney, the electricity supply had failed and the city was plunged into darkness. However, claiming that the Nambour generating plant was one of the most modern in the Commonwealth, he was convinced that if a ‘black-out’ did occur in Nambour, it would be short-lived. Nevertheless, the unforseen demand for power meant that black-outs did occur regularly.

The demand for electricity climbed so rapidly in the Shire that the original 1927 plant could not cope and additional plant was installed. Problems continued as demand increased including overheating of the engines and black-outs, which meant complaints from business customers in particular. With some of its plant output being DC and some AC, the Moreton Central Sugar Mill could not help out. The Shire Council had to apply for another loan from the State Government to replace the plant. The replacement engines were installed in 1932.

1928: New Farm Powerhouse commissioned

A favourite story common to the majority of New Farm employees related to the abundance of prawns, crabs and trevally that they were able to catch in the Brisbane River around the powerhouse. Often, the fresh catch would be barbecued on site for lunch. Sharks also came near to the riverbank, attracted by the warm exhaust water discharged from the plant. ‘In winter months it was quite common to see numbers of sharks up to two metres long basking in the hot water’ said Mr. Wilson. However, there were times when the overload of fish caused problems, too. The river provided the water needed to keep the turbine condensers functioning. Rotating mesh filter screens were fitted in an attempt to stop marine life and other debris blocking the condensers. Nevertheless, small fish could still find a way through and the ends of the condensers had to be taken off for cleaning. Some of the dead fish would have been there for weeks at a time, and a rotting fish smell would permeate the turbine hall. Mr. Wilson recalled, ‘It made the station hard to work in for some time’.

1929: Murgon

Murgon was the second town in the South Burnett to receive an electricity supply. Electricity was generated in the local powerhouse.

Mr. E.B. Young, known as Ernie, was appointed Engineer Manager in July, 1929 in time for two engines supplied by Ruston Hornsby to arrive. When the Powerhouse was complete, the official switching-on ceremony took place on Tuesday, 12 November, 1929. The phrase, ‘out of the darkness cometh light’ was used to describe the happenings at Murgon on the night of the ceremony. A large gathering of residents and visitor, plus the sounds of the Murgon Town Band, made for a lively scene as the final preparations for the switch-on was made. Following a tour of the schools in the area and the official dinner, which was held at the Royal Hotel in Murgon, Mr. R.M. King, Minister for Public Instruction and Works, accompanied by the Director of Education, Mr. B.J. McKenna and Mr. J.B. Edwards, M.L.A. began the speeches.

Mr. King expressed appreciation on being asked to take part in what he described as being ‘a very important function’ for Murgon, which showed that the Murgon people and the Murgon Shire Council ‘were imbued with a strong civic spirit’. Mr. King proceeded to switch on the current and the whole town was flooded with brilliant light. The Murgon Town Band burst into tune again, this time playing the National Anthem.

The council was pleased with the expenditure in connection with the scheme. The total loan received from the Treasurer was £10,000 at six per cent interest for a period of 21 years. The main items and related costs were reported as:

- Powerhouse, £1050

- engines, alternators and auxiliaries, £3688

- switchboard, £539

- reticulation, £1635

- street lights, £90

- house services, £1050

The scheme would finally prove to be slightly over budget. This was justified by the purchase of an oil separator, which would save money on oil purchases. There was a further additional expense with the engineer’s residence. Nevertheless, owing to a clause in the Customs Tariff Regulations, the council was able to secure a larger engine than previously planned.

…the council was fortunate in securing a four-cylinder engine, or 20 per cent more power than the three-cylinder one ordered, the price of the latter being £1787 including 10 per cent duty and for the larger one £1836 duty free. Thus, for £49 a considerable amount of extra or reserve power was obtained.

A small two-cylinder engine was also purchased, mainly to allow the plant to run unattended at night. The Powerhouse plant was guaranteed to carry a 25 per cent overload for two hours at peak load times. Murgon Shire Council was adequately prepared for the growth in demand for electricity in the home, for industries and on the farms in the shire, at least for the foreseeable future.

The Murgon scheme did not show a profit until December 1933. One of the reasons given was the tardiness of potential consumers to appreciate the benefits of electricity even though an eighteen-month advertising campaign had been conducted before the scheme began. When the Powerhouse opened in November, 1929, there were 80 consumers connected to supply. By the end of the following year, there were 163. In 1931, 180 consumers; 201 in 1932; 218 in 1933; 245 in 1934; 258 in 1935 and the number of separate installations by May 1936, when the Royal Commission visited Murgon, amounted to 272.

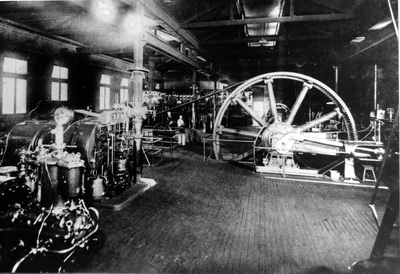

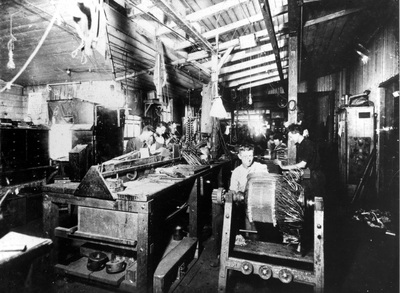

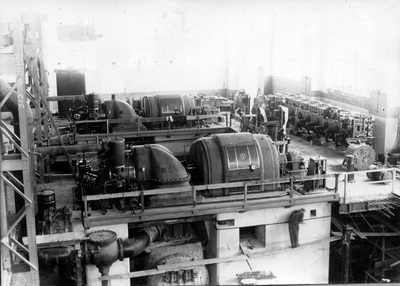

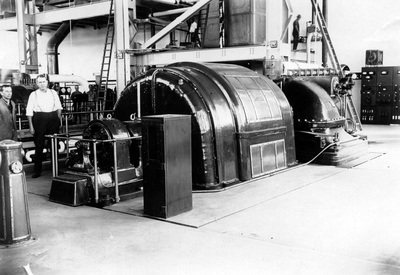

Nambour Powerhouse engine room